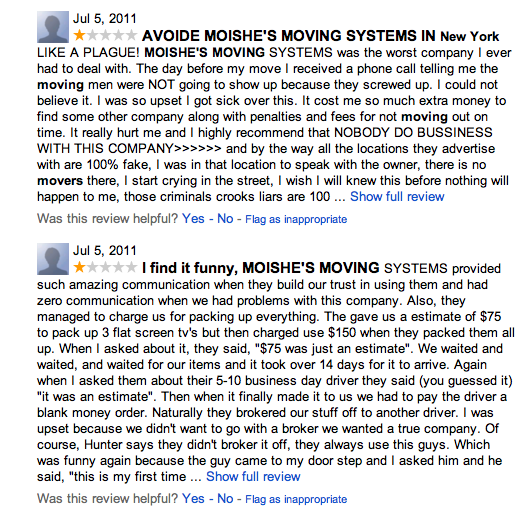

Most small businesses live in dread of the day when a competitor drops a nasty review on their Places page. Imagine waking up one day and finding 58 of them. That’s what happened to the Place Page for Moishe’s Moving Systems in NYC. For several days in early July they were finding one 1 star review after another showing up on their Places page. Imagine their sense of futility as they hit the “flag as inappropriate” link over and over again.

Most small businesses live in dread of the day when a competitor drops a nasty review on their Places page. Imagine waking up one day and finding 58 of them. That’s what happened to the Place Page for Moishe’s Moving Systems in NYC. For several days in early July they were finding one 1 star review after another showing up on their Places page. Imagine their sense of futility as they hit the “flag as inappropriate” link over and over again.

A quick call to their competitors across town indicated the same was happening to them. Not just the same pattern but the very same reviews, same bad English, same mispellings, often not even getting the company name correct.

A search in Maps on the phrase “It really hurt me and I highly recommend that NOBODY DO BUSSINESS WITH THIS COMPANY>>>>>> and by the way all the locations they advertise with are 100% fake” surfaced the very same reviews on over 100 moving companies country wide from Miami to LA.

It seems that in this scam, hundreds of moving companies across the U.S. not only ALL received the exact same bad reviews but many then soon received unsolicited proposals to “remove malicious, old, slanderous, unfounded, and internet defamation ratings”.

The internet has spawned a whole new generation of reputation management firms that help make sure that the front page of Google does not have bad things prominently displayed about your company. With the growing importance of reviews and the impact that they have had on businesses a number of companies jumped into the “positive review” only game to be sure that your Places page showed only glowingly satisifed reviews.

The internet has spawned a whole new generation of reputation management firms that help make sure that the front page of Google does not have bad things prominently displayed about your company. With the growing importance of reviews and the impact that they have had on businesses a number of companies jumped into the “positive review” only game to be sure that your Places page showed only glowingly satisifed reviews.

But apparently, the review reputation management business has taken on a new, more sinister twist of late. It appears that unscrupulous “reputation management” firms are now not only offering to place postive reviews on your Places page and help take down negative reviews, they are actually creating the negative reviews in the first place. Now that’s a business model! Have you seen this practice in other industries?

Google has indicated that they are in the process of removing the reviews. That being said it does highlight the structural problems caused by a still immature review spam algo AND the frustrating process for an SMB to request that a review be removed via the “flag as inappropriate” link. This problem is much like the issues that they confront with bugs in the Places Dashboard process.

It is likely that this obnoxious review spam will be taken down, it is also likely that the spam review filter algo will improve over time.

The current automated flagging system however is inadequate to handle the situation until such time as the algo improves. The flag, like many Google complaint processes, is likely just feedback to their machine learning system. It rarely if ever leads to an immediate takedown. Google consistently prioritizes their needs and the assumed needs of reviewers in this process. It certainly provides NO feedback to the affected merchant as to what if anything Google will do about the problem review.

As demonstrated once again by the review snafu last week, when numerous revews were lost, reviews are an very much a flash point for most business users of Places. The lack of quick public response on Google’s part demonstrated either an incredible lack of staff, an incredible lack of sensitivity or perhaps just an on-going tin ear to the needs of their small business clients vis a vis reviews.

Until such time as the algo is significantly improved and problems like extortion spam can be greatly minimized in an automated fashion Google needs to create a process that comes down in favor of the SMB reporting the problem. Perhaps one that hides the egregious reviews pending a human review process that actually includes timely communication. Once the algo has been refined they could then think about a cut back to the human intervention.

But with Google’s growing portfolio of Local Commerce products they will find a very chilly reception indeed on Main Street until they do a better job of handling reviews.