When it comes to greening our office buildings, we apply the same focus that we use for any of our products: put the user first. We want to create the healthiest work environments possible where Googlers can thrive and innovate. From concept through design, construction and operations, we create buildings that function like living and breathing systems by optimizing access to nature, clean air and daylight.

Since I arrived at Google in 2006, I’ve been part of a team working to create life-sustaining buildings that support the health and productivity of Googlers. We avoid materials that contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other known toxins that may harm human health, so Googlers don’t have to worry about the air they’re breathing or the toxicity of the furniture, carpet or other materials in their workspaces. We also use dual stage air filtration systems to eliminate particulates and remaining VOCs, which further improves indoor air quality.

Since building materials don’t have ingredient labels, we’re pushing the industry to adopt product transparency practices that will lead to real market transformation. In North America, we purchase materials free of the Living Building Challenge Red List Materials and EPA Chemicals of Concern, and through the Pharos Project we ask our suppliers to meet strict transparency requirements.

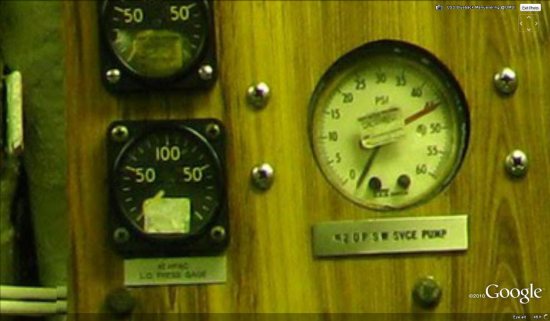

We also strive to shrink our environmental footprint by investing in the most efficient heating, cooling and lighting systems. Throughout many of our offices, we’ve performed energy and water audits and implemented conservation measures to develop best practices that are applied to our offices worldwide. To the extent possible, we seek out renewable sources for the energy that we do use. One of the earliest projects I worked on at Google involved installing the first solar panels on campus back in 2007. They have the capacity to produce 1.6 megawatts of clean, renewable electricity for us, which supplies about 30 percent of our peak energy use on the buildings they cover.

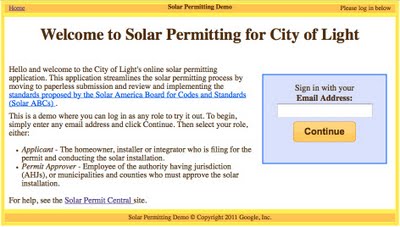

With a little healthy competition, we’ve gotten Google’s offices around the world involved in greening our operations. Our internal Sustainable Pursuit program allows teams to earn points based on their office’s green performance—whether it’s through green cleaning programs, water efficiency or innovative waste management strategies. We use Google Apps to help us track progress toward our goals—which meet or exceed the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED standards—and share what we’ve learned among our global facilities teams.

We’re proud of our latest LEED Platinum achievement for the interior renovation of an office building at the Googleplex. While we have other LEED Platinum buildings in our portfolio, it’s a first for our headquarters and a first for the City of Mountain View. The interior renovation was designed by Boora Architects and built by XL Construction, using healthy building materials and practices. In fact, we now have more than 4.5 million square feet of building space around the world on deck to earn LEED Certification.

via Green blog