If you’ve been following this series of blog posts, you’ll know that I’ve been investigating methods to create an animated background tile layer to display weather maps using the Bing Maps v7 AJAX control.

For this final post, I’m going to wrap everything I’ve done so far into a reusable module.

Bing Maps Custom Modules and the “Ninja” update

The most recent update to the Bing Maps AJAX control, introduced in early May 2011, became slightly notorious as the “ninja” update. The reason being that, silent but deadly, the unannounced update accidentally broke many websites with no warning. Unfortunately, these breaking changes rather eclipsed some of the other nice new features introduced in the update – one of which was the introduction of a common framework through which Bing Maps could be extended by creating custom modules.

Now that the bugs introduced in the latest update have mostly been ironed out, I thought it time to investigate the new module functionality. It’s pretty easy to move your custom code into a module – the main requirement is that, at the end of your function, you place a call to the Microsoft.Maps.moduleLoaded() method. This lets Bing Maps know that your module had been loaded and ready to use.

So, I added the moduleLoaded() call, rolled my animatedTileLayer function into a file and uploaded it to http://www.a3uk.com/bm_modules/animatedtilelayer.js. Note that custom modules registered via the Bing Maps registerModule() method must be placed on a publicly-accessible website – you can’t register a custom module on a local URL. So, when you’re developing a module locally, I recommend that you get it working properly first using a regular embedded script, and then wrap it in a module at the last minute.

To use my new module, I registered and loaded it as follows:

// Register and load the animation module

Microsoft.Maps.registerModule('animatedTileLayerModule', 'http://www.a3uk.com/bm_modules/animatedtilelayer.js');

Microsoft.Maps.loadModule("animatedTileLayerModule", { callback: animationModuleLoaded });

The animationModuleLoaded callback would be fired after the module had loaded, and was responsible for creating a new instance of the animatedTileLayer class and adding it to the map, as follows:

function animationModuleLoaded() {

// Define the array of frame URLs. The URL for the tiles of each frame are

// stored in subdirectories corresponding to each timestamp, named by quadkey

var frames = [

'http://www.a3uk.com/demos/aniamtedtilelayer/tiles/201105271015/{quadkey}.png',

'http://www.a3uk.com/demos/aniamtedtilelayer/tiles/201105271030/{quadkey}.png',

'http://www.a3uk.com/demos/aniamtedtilelayer/tiles/201105271045/{quadkey}.png',

...

];

// Create a new instance of the AnimatedTileLayer class

animatedTileLayer = new AnimatedTileLayer(

map, // Map instance to which tilelayer should be added

frames, // Array of frames of the animation

{

framerate: 1000, // Delay between frame changes (ms)

loopbehaviour: 'loop', // Behaviour when last frame is met

opacity: 1, // Opacity of tile layer

mode: 'dangerous', // Method to use when switching layers

frameChangeCallback: updateFrameCounter // Callback on every frame change

}

);

// Add the tilelayer to the map

map.entities.push(animatedTileLayer);

}

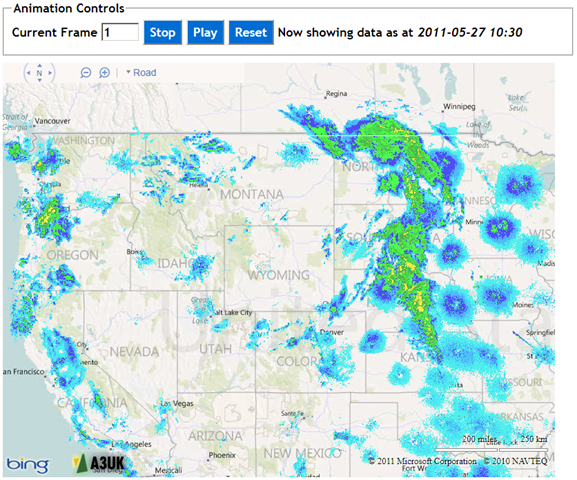

(The options passed to the AnimatedTileLayer constructor are explained in my previous posts). I also added a couple of basic HTML buttons to the page that would control starting, stopping, and resetting the animation, and a text input box that would display the timestamp of the currently displayed frame:

The current frame counter would be updated by the function specified in the frameChangeCallback:

// Callback gets called every time frame changes

function updateFrameCounter(n) {

// Display the frame counter

document.getElementById('frameIndex').value = n;

// Show the timestamp corresponding to this frame

var t = String(timeStamps[n]);

document.getElementById('frameTimeStamp').value = t.substr(0, 4) + '-' + t.substr(4, 2) + '-' + t.substr(6, 2) + ' ' + t.substr(8, 2) + ':' + t.substr(10,2);

}

Put it all together and what have you got?

So that’s it – my animatedtilelayer class wrapped into a custom module, registered and loaded from a page that creates a new animated tile layer and calls into a couple of the methods provided by the class.

You can play with (version 1.0) of the final product at http://www.a3uk.com/demos/animatedtilelayer/:

To Do:

There’s still a few bugs that I’m aware of that, at some point, I might try to fix:

- Memory usage (especially in Firefox) seems to be an issue, and grows substantially if the animation is left running for a while – I’m not sure memory from the old tile layers is properly released following entitycollection.clear(), but I haven’t investigated this fully yet. (This problem is also reported by another user here). IE9 and Chrome appear to fare much better.

- The tile layer vanishes while the map is scrolled (but then reappears when the map has finished scrolling) – this doesn’t seem to be unique to my animated tile layer, but is a behaviour of the way Bing Maps handles custom tile layers in general, so I’m not sure there is anything I can do about it.

- By necessity of my attempt to pre-load the next tilelayer before displaying it on the map (to enable smoother transitions between frames), there is an initial delay after clicking “Play” before the first frame change. Again, I think this might end up being marked as “by design”!

- I’m sure there’s more – I haven’t exactly comprehensively QA’d this module, but you’re free to make use of it as you see fit.