Retired software engineer Peter Olsen discovered SketchUp shortly after it was acquired by Google in 2006. He published his first model to Google Earth’s “3D Buildings” layer in July 2008. Two and a half years later, he has 68 buildings in Google Earth—some as far away as Italy and Peru.

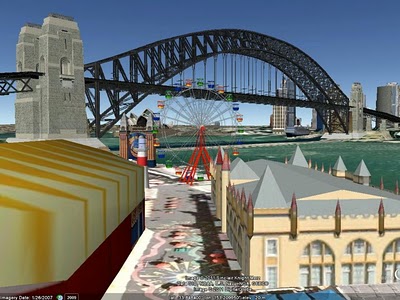

Peter is a Sydneysider, so it’s not surprising that he focused his initial geo-modeling activity in his home town. He’s modeled several of the city’s most visible buildings and structures, including Luna Park, the Anzac Bridge, Pyrmont Bridge and the Sydney monorail.

In addition to the 3D model, he also created a fully animated version of the Luna Park Ferris Wheel (seen above) complete with moving shadow, using a technique pioneered by Barnabu in his London Eye animation.

Peter noticed that many of Australia’s special places had not been modeled, so he expanded his reach by modeling Australia’s unique underground Parliament House building in Canberra, Australia’s capital city.

Like any artist, Peter continued to perfect his skills by tackling more complex geometric structures. Peter says:

“I never lost my interest in architecture and throughout my years in computing I dreamed of the day when a program would be invented that would allow the construction and manipulation of a 3D model of a building. The capability was naturally developed eventually, in the form of very expensive CAD programs. Imagine my absolute delight when I stumbled across a brilliant free program called Sketchup. My years of dreaming had suddenly become a reality.”

In 2010, he modeled one of the most challenging places on earth: Machu Picchu.

Many geo-modelers estimate building heights and other details from photographs. Not Peter. He takes great pride in the accuracy of his work as his description in the Machu Picchu model indicates: “The model contains every building, terrace and staircase and is accurate to less than 10cm (4″) over most of the site.” Peter insists that he likes his “models to be absolutely accurate reproductions, not just approximate representations.”

During email discussions about some of Peter’s Sydney models, I jokingly mentioned that the Google Sydney building had yet to be modelled. Four hours later he forwarded a reasonably accurate model of the building based on a few scant photos of the recently-completed building that he found on the web.

I appreciated his efforts and and invited Peter to lunch at the Google office. After lunch Peter spent 6 hours painstakingly measuring and photographing every nook and cranny of the building (I guess he liked the food!). A week or so later he forwarded his latest work of art, which has since been incorporated into the 3D buildings layer. Peter says that his “sense of amazement at the results that can be achieved with SketchUp has not diminished since the day I started work on my first model.”